Return to

Concert Program and Tickets Online

From Shoe Laces to a Ship

Exclusive interview with Wojciech Świtała,

an international piano competitions prizewinner

by Bożena U. Zaremba

I remember when [Krystian] Zimerman had a master class for our students, he always started the class with the question,“How can I help?” This established the setting of the class right from the start – to see if the student knew what he or she wanted to communicate. If the answer was very enigmatic or if there was no answer at all, this was also a signal. These are elementary questions that any pianist needs to answer.

You have won prizes at many international piano competitions. Which do you value most?

It is difficult to measure them. Each one was important at the moment, because it confirmed that what I do makes sense. To be noticed is always pleasant and leads to concert opportunities. Looking from a distance of some years, I especially value the M. Long-J. Thibaud [International Piano Competition], which is an important competition and which led to many recitals in France and helped me make many connections in the music world. On the other hand, the Chopin [International Piano] Competition, where I received an award for the best performance of a polonaise, was significant, despite the partial success. This competition is so prestigious that it gave me vital recognition in music circles.

There were rumors about your walking out.

But it was really prosaic. The Chopin Competition – 20 years ago – was different. At that time, it was virtually the only ticket to concert halls. We did not have the freedom in Poland and the opportunities that we have now. We, the contestants, were under a lot of pressure; we were told that we were representing Poland and that they were counting on us. After the recent Euro 2012*, we know perfectly well what burdensome baggage this can be. On top of that, there was exhaustion and diabolic stress. There was no balance there. At some point, I remained the only Polish participant, and the pressure was building up. “You must, you must—,” I was told. In this situation my body started to rebel. This was a very difficult decision, but it was solely mine. Everyone has a different mental predisposition. Some people, for example, cannot live without the stage. I can live without the stage. Not without music, though. But I am not complaining.

Controversies often help in building a career. How did this affect yours?

It did not help me, for sure; it only opened the door to speculation, but this was simply a health issue – I just couldn’t. Even if I had achieved great success, I would have reduced public appearances. I was not ready for such a great load. Even these days, I play 20 to 30 concerts a year. That is all I can do. I cannot imagine being forced by a manager to play three recitals here and the next week four there. Chopin played 30 public concerts in his whole life!

So there is nothing to be ashamed of.

Absolutely [laughs]. Not that I can compare to him, but on the other hand—

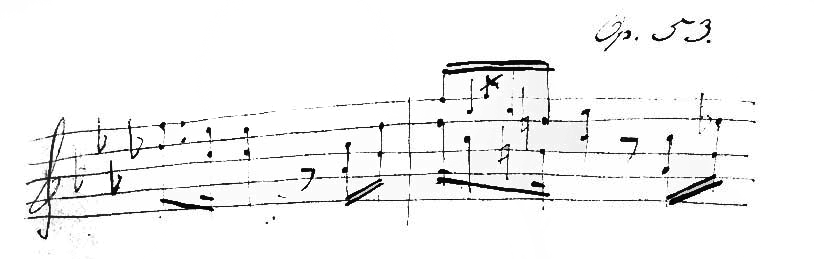

It was for your recording of Chopin’s music that you twice received the prestigious Grand Prix du Disque Frederic Chopin award. The goal of this so-called National Edition was to present Chopin’s work in the most possible authentic version. Why was such historic accuracy so important?

This is a very delicate topic – what is authentic when we talk about the text or what is authentic when we talk about the sound. The research on manuscripts is so advanced, and it has resulted in indisputable discoveries that have verified the notation. Sometimes these are minor corrections, but sometimes, like in the Etude in E major, op. 10, there are significant changes in harmony. Pursuit of authenticity seems to me most sensible, but of course [Artur] Rubinstein’s recordings, for example, do not lose their luster just because he used a different edition. From time to time, I take some liberties as well.

You have also recorded Chopin’s music on the pianos from his time. Tell us about your interest in historical instruments.

This is a strange passion. It all started when the Chopin National Institute [in Warsaw] purchased their first Erard, in 1998 I think, and I was asked to play a recital on this instrument. I had very recently heard such recordings by Emanuel Ax and was enchanted by the mysticism that I sensed there. There is a common conviction that you cannot play on these instruments, that they are not concert instruments, just pretty pieces of furniture at the most. Anyway, I went to Warsaw and was shocked to learn not only that can you play on such an instrument but also that it does not differ from the modern instrument that much. It does require a different touch and sensitivity, but if you make an effort, [with nostalgia] it will take you back in time to the 19th century. This was so beautiful that I started to dream about owning such an instrument.

And you do.

Yes! [with pride]. The story is a bit funny. One of our piano tuners, who knew I was looking for a historical instrument, called me one day and said he saw an Erard on Allegro**. Can you believe it? On Allegro, where you can buy stuff from shoe laces to a ship! I laughed it off at first, but then thought it over and decided to try it out. It turned out to be exactly what I was looking for – an Erard from 1953 – and in a very good condition. It did need some renovation, such as strings and hammer felt, but the mechanism, the action were original.

Without getting too technical, how do those historical instruments – Erards and Pleyels – differ from today’s Steinways or Yamahas?

Generally speaking, since the mid 19th century, the instruments have made adjustments toward bigger concert halls, which entailed bigger and more uniform sound. The instruments Chopin played were meant for small salons and had a sound that was more subdued and uneven. When you play some of Chopin’s preludes on a historical instrument, for example, you do not have to look for certain color because it is already there. You can tell right away that this music was created for this type of an instrument, and notations, such as delicatissimo, are in perfect harmony with the text. The sound in modern pianos is bigger but less selective and less pronounced. If [Franz] Liszt had had a choice, he would probably have preferred a modern piano, which would have given him maximum range. Chopin, however, with his sublime sound and with his fragile physique, would not have been happy sitting at a Bösendorfer. An Erard can sound a bit archaic, but it can help one better understand the structure of Chopin’s work.

These nuances will definitely appeal to listeners who look for the richness of sound. What about those who look for emotional or metaphysical thrills?

They should definitely listen to a Pleyel. All dramatic preludes, for example, are more interesting, more mysterious. On the other hand, the lyrical preludes sound better on a modern piano because on a Pleyel, which has a much shorter sound, it’s difficult to play an extreme legato. This can be a great experience for pianists, because they can appreciate Chopin’s method and soul.

Our conversation is revolving around aesthetics a lot. I sense in you great admiration for beauty.

Yes, you are right. I feel that these days a general appreciation for beauty should be promoted. It is imperative, though difficult. For me, it is a certain kind of a calling and mission, if not just a certain “abreaction” to things that surround us. It is even more important for young people, since in recent years their principles have diminished so much to a materialistic approach.

How did you become a pianist?

My parents were very much into music. My mother was a singer. I still know most of Mozart’s opera arias by heart [laughs]. My father played the piano, but in his traditional Silesian family technical education was more valued so he became an engineer. But music was still a big part of our family life. When I was bored, my parents would place me, a little boy, on a stool, give me a pencil and say, “Now you are the most important person. You are the conductor” [laughs]. When I was around four years old, my mother bumped into her piano teacher from her music school, who convinced her to bring me to private lessons, so I had an excellent teacher right from the start. And that’s how it all began. It turned out that I was musically inclined. It all came to me easily. It’s hard to talk about choices. I did what I was asked to do. At some point I had enough, but I had no courage to tell my parents [laughs]. It was in high school when I started to think about my future, and I felt music was so deeply imbedded in me that I decided this was the thing I could do best.

Besides being a solo pianist, you spend a lot of time playing chamber music. What do you find appealing about it?

It’s a certain kind of a dialogue. You don’t just propose something but also accept other ideas. In my opinion, without the ability to play chamber music, you cannot be flexible in structuring solo performances. You can learn a lot from a good instrumentalist or a vocalist. It’s the breathing; it’s the phrasing.

This is not your first recital in America. What are your expectations this time?

I have high expectations – of myself [laughs]. I want to come perfectly prepared and to stir the audience’s imagination with the program that has been my passion for years.

*European Soccer Championship hosted by Poland and Ukraine in the summer of 2012

**Polish online auction website