About

Upcoming Events

Past Events

Sponsorship

Chopin Notes

Press

Videos

For Youth

About

Upcoming Events

Past Events

Sponsorship

Chopin Notes

Press

Videos

For Youth

Copyright © 2002 - 2016 Chopin Society of Atlanta

No Compromises

Exclusive Interview with

Georgijs Osokins

a finalist at the 2015 Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Exclusive Interview with

Georgijs Osokins

a finalist at the 2015 Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Critics have called you “exceptional,” “unpredictable,” and “original.” Do you identify with these adjectives?

I do agree with the word “unpredictable.” For me it is a compliment, because every time I play, I try to play differently. I think this is overtly the right approach, especially while interpreting Chopin’s music. Chopin himself played like that when he performed. One of his students even remembered that Chopin told him to play exactly like him, but the master’s interpretation changed every time he performed.

I do agree with the word “unpredictable.” For me it is a compliment, because every time I play, I try to play differently. I think this is overtly the right approach, especially while interpreting Chopin’s music. Chopin himself played like that when he performed. One of his students even remembered that Chopin told him to play exactly like him, but the master’s interpretation changed every time he performed.

How do you find a balance between having your own voice and being true to the composer’s intentions?

It is very difficult and subjective for every musician, not only a pianist. I believe that when we play, we naturally express ourselves. We play through the prism of our personality, so naturally every interpretation is different. As a pianist you build your own concept of a particular piece and then present your interpretation to the audience. Some might say that I show my personality too much, but especially with Chopin, who is so close to my heart, it is important to share my vision. For me there are no compromises here.

Some people considered your renditions at the competition too unorthodox.

This, again, is actually a compliment. If your playing is seen as controversial, it is the right way to go. All great musicians, including pianists, must be controversial and must take risks. I know some people—not only the jury members, but critics and audience—loved me; some hated me. And for me it is the best. In the final stage, when all the pianists were very good, it was hard to decide who’s the best, and with Chopin’s music, there is no best pianist anyway, no best interpretation. They are just different. The finalists were all very talented young pianists. Maybe you can say that this time, this pianist played better, was more stable or consistent. But this is not a sport; this is art, and art has its own nature. For example, it is impossible to compare the paintings of Salvador Dali with Rembrandt’s. They are just different.

Did you ever imagine you would get so far in the Chopin competition?

While playing during the different stages, the word “competition” did not exist in my mind. Every time I played, I tried to feel the energy of the concert hall, and I played for the audience. It was just as if I was playing the first, second and third recital. An atmosphere of competitiveness is the most evil thing for art, as Glenn Gould said. So I completely abstracted myself from the competition. While playing, I was far away. For me the most important stage was the first one, in October [2015]. Playing in the legendary concert hall, in front of the most admired musicians and pianists in the jury, was quite nerve-wracking. I knew that if they accepted my way of interpreting Chopin at that point, I could go very far.

The press noted the extensive coverage of the competition on social media. What do you think about this fairly new method of disseminating information?

I am not a pianist who loves attention on social media. I just don’t like publicity. I don’t even have a Facebook or other social media account. This exhibitionism is a bit disturbing for me. I want to concentrate on music, sometimes even isolate myself from the outside world. I think being reserved is good for an artist; it’s good for his music. But you have to deal with it. On the other hand, every possible recording, made throughout the history, can now be so easily accessed. And it influences peoples’ perception. Now you can form an opinion about a pianist after listening to his or her on YouTube for only 30 seconds.

How did you prepare yourself to the competition?

I prepared quite extensively because if you have a competition which happens only once every five years and which is very unique, and then you have to prepare compositions by only one composer, which is also very rare, you need to start working on it quite in advance. So my preparations lasted for at least three years. During the last year before the competition, I played only Chopin. I believe you need to immerse yourself into his world and forget about everything else. Really. And I think it worked. It’s like famous movie directors, like genius directors whom I admire, such as Andrei Tarkovsky, who would work on one movie for a very long time. I adopted the same strategy. When you have something very important, you just need to close your eyes to everything else.

You also spent a lot of time studying Chopin’s life and his era. What did you find inspiring about the composer’s life?

There are several things that I found fascinating. I think he reached a high level of maturity, not only as a composer but also as a human being, enormously early. Through his life experiences, he was already an old man in his early twenties. And at that age, his compositions were so difficult and his music language so sophisticated. He lived quite a tragic life; he left his country at a terrible time, and this had a tremendous influence on his music. Every pianist needs to be aware of this. You also have to know Poland, the Polish people, and Polish folklore to understand what Chopin wanted to convey in his music. Then we need to remember that while writing this wonderful music, he was ill. He must have been very strong in spirit. I admire him for that.

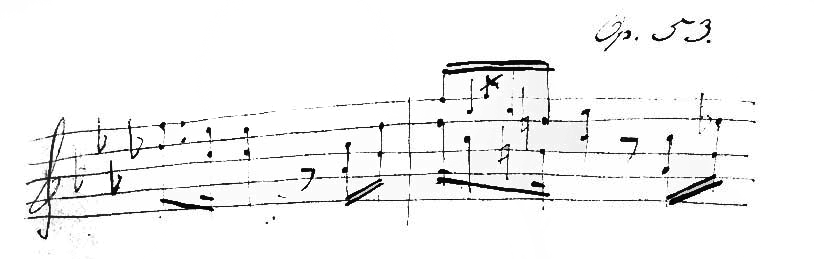

What do you admire about his music?

I feel an emotional connection to his music. It is very special to me, though I cannot say I like every single piece. I think that no pianist who wants to be honest would say that he or she likes all works of a particular composer. In terms of Chopin, his pieces are so individual, so special and unique. What I love about Chopin is that there is so much symbolism in his music, even more than in Bach, whom Chopin admired. For example, Chopin often used the symbol of a cross, which is very important in the development of Polonaise-Fantasie [in A-flat major, Op. 61], but he also built his own system of symbols, not so visible and obvious. His language overall is difficult and complex, and his compositions, especially late ones, are extremely well structured, like Beethoven’s. He never has problems with structure (unlike Schumann or Liszt, for example, who did have such problems). In what I call “architecture” or “tectonics,” he was simply a genius. His every piece is like gold, is so perfect. This is very unique. His language is very interesting in developing the tonality and musical motifs. And then the melody connection is just wonderful. On top of that there is so much freedom in his music. It is all breathtaking.

You come from a family full of professional musicians. Did you ever want to be someone else?

I really had no choice, but not in a negative way. I basically grew up under a piano. My parents had a small apartment with a German grand piano. My mother, my father and my brother all played this piano all day long. Music was my life, and it was natural for me to become a pianist. At the age of four or five, I started to play, and it came very easily. What is important is that I started to play in public early. These were small concerts, but I instantly felt comfortable on stage. I can’t say that I am not nervous, but because I started performing at an early age, I feel comfortable. This whole process of becoming a musician was very natural for me. I have also composed some small pieces for movies and documentaries, and some just for myself. I think that every pianist should compose and should be able to improvise. Last year I also started conducting. It influences the way you play. I think that a musician should be able to do everything and develop all aspects of music. Listening to some pieces for choir, for example, helped me understand Chopin better, and the vocal nature of his music in particular.

Where do you see yourself 20 or 30 years from now?

We pianists must be grateful because we achieve the highest level of playing late in life, when we are around 50 years old. The career of ballet dancers, for example, is so quick, so ephemeral. A ballet dancer is like a butterfly, while some genius pianists are at their best even in their 70s or even 80s. Look at Horowitz or Rachmaninoff. I hope my life will give me strength to develop musically.

Tell us something about your interests outside of music.

My inspirations come from different genres of art. I like literature, visual arts and movies. I build my own conception for every musical piece through the use of my imagination, which I feed with my fantasies inspired by books and great paintings. I am also passionate about sport and am an avid tennis player. I started playing early, and at 12 I played competitively, even internationally. Now I only do it recreationally. Tennis is good for your muscles, and your spine (if you do it right). It is my favorite sport also because, just like on stage, you are completely on your own. You need to think about your strategy, and you often have to overcome your weaknesses and find your path. Everyone has good days and bad days, and you need to learn how to make adjustments—mentally, physically and emotionally. I think that tennis helped me develop these skills. I agree with a saying that the pianist’s stage is the loneliest place on earth. You are in your own world, with your imagination, with no help, no compass. And I believe it must be so.

It is very difficult and subjective for every musician, not only a pianist. I believe that when we play, we naturally express ourselves. We play through the prism of our personality, so naturally every interpretation is different. As a pianist you build your own concept of a particular piece and then present your interpretation to the audience. Some might say that I show my personality too much, but especially with Chopin, who is so close to my heart, it is important to share my vision. For me there are no compromises here.

Some people considered your renditions at the competition too unorthodox.

This, again, is actually a compliment. If your playing is seen as controversial, it is the right way to go. All great musicians, including pianists, must be controversial and must take risks. I know some people—not only the jury members, but critics and audience—loved me; some hated me. And for me it is the best. In the final stage, when all the pianists were very good, it was hard to decide who’s the best, and with Chopin’s music, there is no best pianist anyway, no best interpretation. They are just different. The finalists were all very talented young pianists. Maybe you can say that this time, this pianist played better, was more stable or consistent. But this is not a sport; this is art, and art has its own nature. For example, it is impossible to compare the paintings of Salvador Dali with Rembrandt’s. They are just different.

Did you ever imagine you would get so far in the Chopin competition?

While playing during the different stages, the word “competition” did not exist in my mind. Every time I played, I tried to feel the energy of the concert hall, and I played for the audience. It was just as if I was playing the first, second and third recital. An atmosphere of competitiveness is the most evil thing for art, as Glenn Gould said. So I completely abstracted myself from the competition. While playing, I was far away. For me the most important stage was the first one, in October [2015]. Playing in the legendary concert hall, in front of the most admired musicians and pianists in the jury, was quite nerve-wracking. I knew that if they accepted my way of interpreting Chopin at that point, I could go very far.

The press noted the extensive coverage of the competition on social media. What do you think about this fairly new method of disseminating information?

I am not a pianist who loves attention on social media. I just don’t like publicity. I don’t even have a Facebook or other social media account. This exhibitionism is a bit disturbing for me. I want to concentrate on music, sometimes even isolate myself from the outside world. I think being reserved is good for an artist; it’s good for his music. But you have to deal with it. On the other hand, every possible recording, made throughout the history, can now be so easily accessed. And it influences peoples’ perception. Now you can form an opinion about a pianist after listening to his or her on YouTube for only 30 seconds.

How did you prepare yourself to the competition?

I prepared quite extensively because if you have a competition which happens only once every five years and which is very unique, and then you have to prepare compositions by only one composer, which is also very rare, you need to start working on it quite in advance. So my preparations lasted for at least three years. During the last year before the competition, I played only Chopin. I believe you need to immerse yourself into his world and forget about everything else. Really. And I think it worked. It’s like famous movie directors, like genius directors whom I admire, such as Andrei Tarkovsky, who would work on one movie for a very long time. I adopted the same strategy. When you have something very important, you just need to close your eyes to everything else.

You also spent a lot of time studying Chopin’s life and his era. What did you find inspiring about the composer’s life?

There are several things that I found fascinating. I think he reached a high level of maturity, not only as a composer but also as a human being, enormously early. Through his life experiences, he was already an old man in his early twenties. And at that age, his compositions were so difficult and his music language so sophisticated. He lived quite a tragic life; he left his country at a terrible time, and this had a tremendous influence on his music. Every pianist needs to be aware of this. You also have to know Poland, the Polish people, and Polish folklore to understand what Chopin wanted to convey in his music. Then we need to remember that while writing this wonderful music, he was ill. He must have been very strong in spirit. I admire him for that.

What do you admire about his music?

I feel an emotional connection to his music. It is very special to me, though I cannot say I like every single piece. I think that no pianist who wants to be honest would say that he or she likes all works of a particular composer. In terms of Chopin, his pieces are so individual, so special and unique. What I love about Chopin is that there is so much symbolism in his music, even more than in Bach, whom Chopin admired. For example, Chopin often used the symbol of a cross, which is very important in the development of Polonaise-Fantasie [in A-flat major, Op. 61], but he also built his own system of symbols, not so visible and obvious. His language overall is difficult and complex, and his compositions, especially late ones, are extremely well structured, like Beethoven’s. He never has problems with structure (unlike Schumann or Liszt, for example, who did have such problems). In what I call “architecture” or “tectonics,” he was simply a genius. His every piece is like gold, is so perfect. This is very unique. His language is very interesting in developing the tonality and musical motifs. And then the melody connection is just wonderful. On top of that there is so much freedom in his music. It is all breathtaking.

You come from a family full of professional musicians. Did you ever want to be someone else?

I really had no choice, but not in a negative way. I basically grew up under a piano. My parents had a small apartment with a German grand piano. My mother, my father and my brother all played this piano all day long. Music was my life, and it was natural for me to become a pianist. At the age of four or five, I started to play, and it came very easily. What is important is that I started to play in public early. These were small concerts, but I instantly felt comfortable on stage. I can’t say that I am not nervous, but because I started performing at an early age, I feel comfortable. This whole process of becoming a musician was very natural for me. I have also composed some small pieces for movies and documentaries, and some just for myself. I think that every pianist should compose and should be able to improvise. Last year I also started conducting. It influences the way you play. I think that a musician should be able to do everything and develop all aspects of music. Listening to some pieces for choir, for example, helped me understand Chopin better, and the vocal nature of his music in particular.

Where do you see yourself 20 or 30 years from now?

We pianists must be grateful because we achieve the highest level of playing late in life, when we are around 50 years old. The career of ballet dancers, for example, is so quick, so ephemeral. A ballet dancer is like a butterfly, while some genius pianists are at their best even in their 70s or even 80s. Look at Horowitz or Rachmaninoff. I hope my life will give me strength to develop musically.

Tell us something about your interests outside of music.

My inspirations come from different genres of art. I like literature, visual arts and movies. I build my own conception for every musical piece through the use of my imagination, which I feed with my fantasies inspired by books and great paintings. I am also passionate about sport and am an avid tennis player. I started playing early, and at 12 I played competitively, even internationally. Now I only do it recreationally. Tennis is good for your muscles, and your spine (if you do it right). It is my favorite sport also because, just like on stage, you are completely on your own. You need to think about your strategy, and you often have to overcome your weaknesses and find your path. Everyone has good days and bad days, and you need to learn how to make adjustments—mentally, physically and emotionally. I think that tennis helped me develop these skills. I agree with a saying that the pianist’s stage is the loneliest place on earth. You are in your own world, with your imagination, with no help, no compass. And I believe it must be so.