Copyright © 2002 - 2017 Chopin Society of Atlanta

Music Saved His Life

Exclusive Interview with

Andrzej Szpilman

Guest of Honor at the 2014 Annual Chopin Society of Atlanta Gala

by Bożena U. Zaremba

Exclusive Interview with

Andrzej Szpilman

Guest of Honor at the 2014 Annual Chopin Society of Atlanta Gala

by Bożena U. Zaremba

The Pianist (2002)—an Academy Award-winning movie by Roman Polański—won the hearts of the audiences worldwide by telling a heart-rending story of a famous Polish pianist, composer and Holocaust survivor Władysław Szpilman. His son, Andrzej Szpilman, a practicing dentist, musician, composer and music producer, initiated the German and English publication of his father’s memoir on which the movie is based. It was translated into 34 languages and sold millions of copies. He later assisted in the production and distribution of the movie and is currently working on a Broadway production of The Pianist.

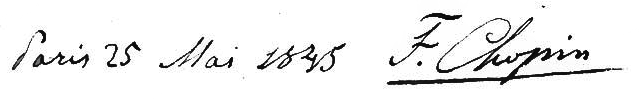

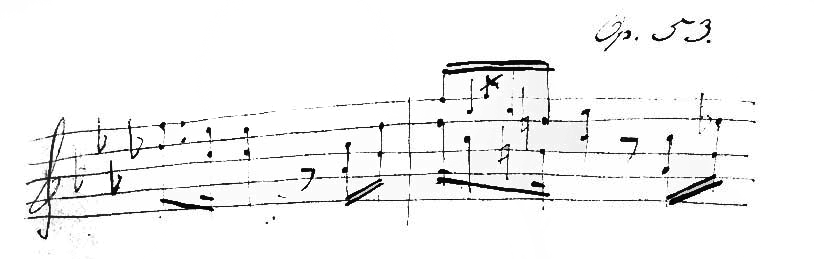

During the last live concert aired by Polish Radio at the very beginning of World War II, your father played Chopin’s’ Nocturne in C sharp minor. He played the same piece in front of the German officer1, one of many people who saved his life, and then during the first program, when Polish Radio reconvened after the war.

And let me add that in 1951, when the first experimental television show was broadcast on Polish TV, he played this very same nocturne. Even though my father, after the war, was never a member of the Communist Party or any pro-government organizations, he became part of Polish Radio. The management built the team with pre-war personnel, and for them, Chopin was an integral part of the everyday program. At that time, it was forbidden to stop Chopin’s music, or let it fade away, or interrupt it by an hourly announcement or time signal. If they did not make it before the top of the hour, they would not make the announcement. Nobody dared cut his music, or talk over it. Chopin was sacred.

What role did Chopin’s music play in your father’s life?

I can say this very clearly. My father was a student of Artur Schnabel in Berlin and, before that, of Józef Śmidowicz and Aleksander Michałowski. All of them were—either in second or third line—students of either Liszt or Chopin himself. So there is a direct connection. My father was considered to be an exceptional Chopin player. The problem was that after the war, he was too fragile for a solo career and he hated travelling by himself. The five years of the war, including three years in complete solitude, left a considerable scar on his psyche. So from 1963, he focused on chamber music. Travelling with four other guys was a completely different life; he did not feel lonely. They gave thousands of performances all over the world, including two U.S. tours. Anyway, my father’s interpretations of Chopin’s music were absolutely classic, in the same tradition as [Arthur] Rubinstein, with whom he was close friend. Chopin cannot be played in any other way. My father understood this very well. I grew up sitting under my father’s Steinway and listening to him play Chopin. It goes without saying that no composer ever composed anything superior for the piano to what Chopin wrote. He was a genius.

Music actually saved your father’s life.

Absolutely, and it was not just because he played in front of that German officer. Let’s face it, that German saved many lives, both Catholic and Jewish, and would have saved him anyway. [Hosenfeld] saved my father not because he played Chopin, but because [Hosenfeld] was a righteous man. And he was a civilized man, who did not agree with the murders that were going on in Poland. He was living like an animal, and the music he heard was as important as air to breathe. At this moment he needed to hear music to endure, to live. And my father provided that. But I think music saved his life in a sense that it gave him the strength and will to survive.

This was not the only time that music saved his life during the war; he supported himself and the whole family playing music.

That’s right. He played a lot—classical music, jazz and pop. He also arranged classical and popular music for two pianos and composed songs for his programs at Warsaw Ghetto cafés. Many of those songs are still played in today’s Poland.

There is a scene in the book where your father, uncle and grandfather miss a curfew and are stopped by a German patrol. But they let them free when one of the German soldiers learns they are musicians. “I am a musician, too,” he says.

Because music is universal. It is not connected with any language. I must say that I have practiced dentistry for many years and get to know people very closely. I notice that in the families where music plays an important role in the family life, where kids learn to play an instrument, the bond between children and parents is in the forefront. Where there is no music, parents at some point become superfluous and lose a vital role in the kids’ lives. I have two children, whom I have raised by myself, and I always made sure they studied music. I can tell that both my daughter and my son are very close to me.

Research about the so-called Mozart effect is widely known, but it concentrates on the intellectual abilities, such as memory, concept grasping, making associations, etc., but not so much on the emotions.

I have recently read about new findings showing that learning music at a young age develops certain areas in the human brain, which would never exist without the contact with music. In the 19th century, in Germany (where I live today), there was a great tradition of cultivating chamber music. Quite often there was no money to build big concert halls, so in every city, big or small, a lawyer would meet in the evening with a physician and a pharmacist and they would play together in the circle of the family. Later this tradition disappeared. I was raised with the love of music, and this is how I raised my children. I believe they greatly benefited from this.

Music can also bring comfort at difficult times. Your grandfather, when he was depressed, would take up his violin and play for hours. This would help him to get away from the horrors of the war and to endure.

I will go further. When I look at the music my father wrote at different moments of this life, I see intense creative drive at the most difficult moments: in 1933, when Hitler came to power and my father had to leave Berlin; in 1940, when the Warsaw Ghetto was created; then during the 1968 anti-Semitic period, when he was not allowed to travel and was harassed by secret police. The trauma shows in the orchestral music he composed at those times.

What about happy moments?

Then he wrote popular songs. He could write a song anywhere, while sitting at a café table, for example. Recently I found a napkin on which he wrote “The Red Bus.”2 He never approved of my song writing, though. He was afraid that if I was a successful song writer, I’d give up my medical studies.

Why didn’t you devote your career to music?

I never treated music career seriously, although I did have some success. I played the violin for 12 years, but I thought I never had enough talent to be an artist, especially because at my school there were so many talented friends. When I was 16, a friend of mine who worked at Polish Radio convinced me to write a song, which unexpectedly for me became a hit. Later I became a music producer, but when you ask me what my profession is, I always say I am a dentist. You need to be really daring to claim to be a composer after having written a few songs and some film music. I am not a musician.

Your father had an exceptional talent.

Yes, he could play any kind of music genre, whether it was jazz, classical music or pop. A friend of mine told me once that at the music festival in Salzburg, a pianist got sick and my father replaced him at the last minute—sight-reading—and accompanied a cello player in cello sonatas. My father never talked about [this incident] because he would have to pay royalties to the Polish art agency. [Laughs.] He read music like one reads a newspaper.

Let me tell you another story. My father was head of the pop music department at Polish Radio and his responsibility was to approve new music for recording. Some people accused him of being unjust, but he was just very demanding. Some composers, after being rejected by my father, would change the key of the song, change the lyrics and the name of the composer and bring it back to my father. He would just glance at it while walking the radio hall and say, “No, no, I saw this already last year; it’s no good.” He heard it in his head. He had a very thorough music education. He could do everything and anything.

Let’s go back to the book and to your father’s account of reciting music in his head. He did it just to exercise his brain and to keep sanity.

This is very true. This made it possible for him to return quickly to touring and recording right after the war. He had an incredible memory and still had an extraordinary technical prowess despite the five-year break. The possibility to practice his broad repertoire just in his head helped him overcome the physical immobility. He survived thanks to an inner drive and certain discipline, typical for performers. Now I see this in my mother, who at 86 still cooks for herself and runs errands. This is admirable. This inner discipline helps people live and survive. When my father was in hiding, he would wind his watch every day to keep some sort of a routine. This gave him a sense that he was alive and that he was not an animal.

When did you learn about your father’s war experiences?

At the age of 12, I found his book by accident, hidden at home. It was just lying somewhere on the shelf. Once I started to read it, I couldn’t put it away. It reads like a thriller. I was totally under its spell, but back then I did not realize it was a story of my family. Many of my father’s friends—composers, conductors, actors and singers—came to our house after the war: Witold Lutosławski, Andrzej Bogucki and his wife, Janina Godlewska, Czesław Lewicki, Helena Malinowska-Lewicka, Władyslaw Bartoszewski (one of the Żegota3 leaders) and many others, but at this time I never knew they were constantly saving his life during the war. My father did not survive just because of this one German officer but because of hundreds of people who collected money and risked their lives to help my father. Also several friends from Polish Radio: Rudnicki, Perkowski, the Boguckis, and Witold Lutosławski, who together with Eugenia Umińska organized concerts to support my father4. They never expected to be paid back or thanked. They helped because they felt the need to do it. These were musicians and, again, music—a common denominator—saved his life.

How did you get the book published in the West?

First, just three chapters were published in Germany, and then my friend connected me with a translator, who translated the whole book for me. I also found a publisher. But the story of the English version is more interesting. Another friend of mine, Roy Kirkdorffer, found for me a literary agent in London. It was Christopher Little. I went there and while waiting for him to see me, I sat next to this lady. He introduces us and says he is going to publish her book. “And we will make a movie. You will see, it will be a great hit. We will have another book then.” It turned out it was J.R. Rowling, who brought the first book of the Harry Potter series! [Laughs.] He was representing The Pianist within a short period of time and brought it to the public first in London and then in New York. The book became a bestseller. It happened that Polański’s lawyer read it, called Polański and said, “This is going to be your next movie.” Polański called my father, then me. This is how the most important movie about those times came into life. I must admit that Polański was my candidate number one to make this movie, not only because of his phenomenal achievement in film, but also because he lived during the [Nazi occupation of Poland]; he had seen it with his own eyes, and he could tell the truth without making too much effort. This is an essential movie not only for the Jews but for all Poles. It shows the truth about the experience and suffering of the Polish nations. It shows the death of Warsaw and the murder of the Polish Jews, which meant the destruction of Polish culture. Jews had been part of that for hundreds of years, and I hope that the new Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw will raise awareness of this relationship.5

What are your reflections about this whole venture?

I have peace of mind now because I lived through the anticipation for my father’s book and then for the movie. I feel fulfilled. We have built sort of a monument in honor of all victims of World War II, while considering the role music played in history.

1 In the movie, he plays Ballade No. 1 in G minor, as Polański did not want to overuse the theme.

2 A pop hit written in 1952 about a Warsaw city bus.

3 Code name for the Polish Council to Aid Jews, an organization established in 1942 by the Polish Underground authorities to help the Jews in Poland.

4 Many of them were recognized as the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for aiding Jews during World War II. So was the German officer Wilm Hosenfeld.

5 Andrzej Szpilman has donated to the Museum a few items that belonged to his father.

And let me add that in 1951, when the first experimental television show was broadcast on Polish TV, he played this very same nocturne. Even though my father, after the war, was never a member of the Communist Party or any pro-government organizations, he became part of Polish Radio. The management built the team with pre-war personnel, and for them, Chopin was an integral part of the everyday program. At that time, it was forbidden to stop Chopin’s music, or let it fade away, or interrupt it by an hourly announcement or time signal. If they did not make it before the top of the hour, they would not make the announcement. Nobody dared cut his music, or talk over it. Chopin was sacred.

What role did Chopin’s music play in your father’s life?

I can say this very clearly. My father was a student of Artur Schnabel in Berlin and, before that, of Józef Śmidowicz and Aleksander Michałowski. All of them were—either in second or third line—students of either Liszt or Chopin himself. So there is a direct connection. My father was considered to be an exceptional Chopin player. The problem was that after the war, he was too fragile for a solo career and he hated travelling by himself. The five years of the war, including three years in complete solitude, left a considerable scar on his psyche. So from 1963, he focused on chamber music. Travelling with four other guys was a completely different life; he did not feel lonely. They gave thousands of performances all over the world, including two U.S. tours. Anyway, my father’s interpretations of Chopin’s music were absolutely classic, in the same tradition as [Arthur] Rubinstein, with whom he was close friend. Chopin cannot be played in any other way. My father understood this very well. I grew up sitting under my father’s Steinway and listening to him play Chopin. It goes without saying that no composer ever composed anything superior for the piano to what Chopin wrote. He was a genius.

Music actually saved your father’s life.

Absolutely, and it was not just because he played in front of that German officer. Let’s face it, that German saved many lives, both Catholic and Jewish, and would have saved him anyway. [Hosenfeld] saved my father not because he played Chopin, but because [Hosenfeld] was a righteous man. And he was a civilized man, who did not agree with the murders that were going on in Poland. He was living like an animal, and the music he heard was as important as air to breathe. At this moment he needed to hear music to endure, to live. And my father provided that. But I think music saved his life in a sense that it gave him the strength and will to survive.

This was not the only time that music saved his life during the war; he supported himself and the whole family playing music.

That’s right. He played a lot—classical music, jazz and pop. He also arranged classical and popular music for two pianos and composed songs for his programs at Warsaw Ghetto cafés. Many of those songs are still played in today’s Poland.

There is a scene in the book where your father, uncle and grandfather miss a curfew and are stopped by a German patrol. But they let them free when one of the German soldiers learns they are musicians. “I am a musician, too,” he says.

Because music is universal. It is not connected with any language. I must say that I have practiced dentistry for many years and get to know people very closely. I notice that in the families where music plays an important role in the family life, where kids learn to play an instrument, the bond between children and parents is in the forefront. Where there is no music, parents at some point become superfluous and lose a vital role in the kids’ lives. I have two children, whom I have raised by myself, and I always made sure they studied music. I can tell that both my daughter and my son are very close to me.

Research about the so-called Mozart effect is widely known, but it concentrates on the intellectual abilities, such as memory, concept grasping, making associations, etc., but not so much on the emotions.

I have recently read about new findings showing that learning music at a young age develops certain areas in the human brain, which would never exist without the contact with music. In the 19th century, in Germany (where I live today), there was a great tradition of cultivating chamber music. Quite often there was no money to build big concert halls, so in every city, big or small, a lawyer would meet in the evening with a physician and a pharmacist and they would play together in the circle of the family. Later this tradition disappeared. I was raised with the love of music, and this is how I raised my children. I believe they greatly benefited from this.

Music can also bring comfort at difficult times. Your grandfather, when he was depressed, would take up his violin and play for hours. This would help him to get away from the horrors of the war and to endure.

I will go further. When I look at the music my father wrote at different moments of this life, I see intense creative drive at the most difficult moments: in 1933, when Hitler came to power and my father had to leave Berlin; in 1940, when the Warsaw Ghetto was created; then during the 1968 anti-Semitic period, when he was not allowed to travel and was harassed by secret police. The trauma shows in the orchestral music he composed at those times.

What about happy moments?

Then he wrote popular songs. He could write a song anywhere, while sitting at a café table, for example. Recently I found a napkin on which he wrote “The Red Bus.”2 He never approved of my song writing, though. He was afraid that if I was a successful song writer, I’d give up my medical studies.

Why didn’t you devote your career to music?

I never treated music career seriously, although I did have some success. I played the violin for 12 years, but I thought I never had enough talent to be an artist, especially because at my school there were so many talented friends. When I was 16, a friend of mine who worked at Polish Radio convinced me to write a song, which unexpectedly for me became a hit. Later I became a music producer, but when you ask me what my profession is, I always say I am a dentist. You need to be really daring to claim to be a composer after having written a few songs and some film music. I am not a musician.

Your father had an exceptional talent.

Yes, he could play any kind of music genre, whether it was jazz, classical music or pop. A friend of mine told me once that at the music festival in Salzburg, a pianist got sick and my father replaced him at the last minute—sight-reading—and accompanied a cello player in cello sonatas. My father never talked about [this incident] because he would have to pay royalties to the Polish art agency. [Laughs.] He read music like one reads a newspaper.

Let me tell you another story. My father was head of the pop music department at Polish Radio and his responsibility was to approve new music for recording. Some people accused him of being unjust, but he was just very demanding. Some composers, after being rejected by my father, would change the key of the song, change the lyrics and the name of the composer and bring it back to my father. He would just glance at it while walking the radio hall and say, “No, no, I saw this already last year; it’s no good.” He heard it in his head. He had a very thorough music education. He could do everything and anything.

Let’s go back to the book and to your father’s account of reciting music in his head. He did it just to exercise his brain and to keep sanity.

This is very true. This made it possible for him to return quickly to touring and recording right after the war. He had an incredible memory and still had an extraordinary technical prowess despite the five-year break. The possibility to practice his broad repertoire just in his head helped him overcome the physical immobility. He survived thanks to an inner drive and certain discipline, typical for performers. Now I see this in my mother, who at 86 still cooks for herself and runs errands. This is admirable. This inner discipline helps people live and survive. When my father was in hiding, he would wind his watch every day to keep some sort of a routine. This gave him a sense that he was alive and that he was not an animal.

When did you learn about your father’s war experiences?

At the age of 12, I found his book by accident, hidden at home. It was just lying somewhere on the shelf. Once I started to read it, I couldn’t put it away. It reads like a thriller. I was totally under its spell, but back then I did not realize it was a story of my family. Many of my father’s friends—composers, conductors, actors and singers—came to our house after the war: Witold Lutosławski, Andrzej Bogucki and his wife, Janina Godlewska, Czesław Lewicki, Helena Malinowska-Lewicka, Władyslaw Bartoszewski (one of the Żegota3 leaders) and many others, but at this time I never knew they were constantly saving his life during the war. My father did not survive just because of this one German officer but because of hundreds of people who collected money and risked their lives to help my father. Also several friends from Polish Radio: Rudnicki, Perkowski, the Boguckis, and Witold Lutosławski, who together with Eugenia Umińska organized concerts to support my father4. They never expected to be paid back or thanked. They helped because they felt the need to do it. These were musicians and, again, music—a common denominator—saved his life.

How did you get the book published in the West?

First, just three chapters were published in Germany, and then my friend connected me with a translator, who translated the whole book for me. I also found a publisher. But the story of the English version is more interesting. Another friend of mine, Roy Kirkdorffer, found for me a literary agent in London. It was Christopher Little. I went there and while waiting for him to see me, I sat next to this lady. He introduces us and says he is going to publish her book. “And we will make a movie. You will see, it will be a great hit. We will have another book then.” It turned out it was J.R. Rowling, who brought the first book of the Harry Potter series! [Laughs.] He was representing The Pianist within a short period of time and brought it to the public first in London and then in New York. The book became a bestseller. It happened that Polański’s lawyer read it, called Polański and said, “This is going to be your next movie.” Polański called my father, then me. This is how the most important movie about those times came into life. I must admit that Polański was my candidate number one to make this movie, not only because of his phenomenal achievement in film, but also because he lived during the [Nazi occupation of Poland]; he had seen it with his own eyes, and he could tell the truth without making too much effort. This is an essential movie not only for the Jews but for all Poles. It shows the truth about the experience and suffering of the Polish nations. It shows the death of Warsaw and the murder of the Polish Jews, which meant the destruction of Polish culture. Jews had been part of that for hundreds of years, and I hope that the new Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw will raise awareness of this relationship.5

What are your reflections about this whole venture?

I have peace of mind now because I lived through the anticipation for my father’s book and then for the movie. I feel fulfilled. We have built sort of a monument in honor of all victims of World War II, while considering the role music played in history.

1 In the movie, he plays Ballade No. 1 in G minor, as Polański did not want to overuse the theme.

2 A pop hit written in 1952 about a Warsaw city bus.

3 Code name for the Polish Council to Aid Jews, an organization established in 1942 by the Polish Underground authorities to help the Jews in Poland.

4 Many of them were recognized as the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for aiding Jews during World War II. So was the German officer Wilm Hosenfeld.

5 Andrzej Szpilman has donated to the Museum a few items that belonged to his father.

Copyright © 2014

Szpilman Archives

View photos of Władysław Szpilman and his son Andrzej