Copyright © 2002 - 2019 Chopin Society of Atlanta

Walking a Fine Line

Exclusive Interview with

MARGARITA SHEVCHENKO

Winner of the 1995 Cleveland International Piano Competition and top prize winner at the 12th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw.

by Bożena U. Zaremba

In addition to winning top prizes at numerous piano competitions, you have won special prizes for your renditions of Chopin’s music. You are also universally praised for your Chopin interpretations. What makes a pianist a “Chopin specialist”?

It is really hard to explain. First of all, you need to love Chopin’s music. You should also try to learn about Chopin as much as possible and to understand his personality. Qualities such as sensitivity and “natural” feeling for his music are helpful, too, but the ability to learn from an expert is most important. I have been teaching a lot of different students and can tell that those students who have imagination and the capacity to intuitively understand what the teacher means are most successful in learning how to play Chopin. It is essential to have a good teacher. I was fortunate to study with Vera Gornostayeva1, who was not only an expert on Chopin but also an amazing teacher. She would say just a few sentences, and suddenly everything was clear. Or she would demonstrate how to play. At that

Exclusive Interview with

MARGARITA SHEVCHENKO

Winner of the 1995 Cleveland International Piano Competition and top prize winner at the 12th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw.

by Bożena U. Zaremba

In addition to winning top prizes at numerous piano competitions, you have won special prizes for your renditions of Chopin’s music. You are also universally praised for your Chopin interpretations. What makes a pianist a “Chopin specialist”?

It is really hard to explain. First of all, you need to love Chopin’s music. You should also try to learn about Chopin as much as possible and to understand his personality. Qualities such as sensitivity and “natural” feeling for his music are helpful, too, but the ability to learn from an expert is most important. I have been teaching a lot of different students and can tell that those students who have imagination and the capacity to intuitively understand what the teacher means are most successful in learning how to play Chopin. It is essential to have a good teacher. I was fortunate to study with Vera Gornostayeva1, who was not only an expert on Chopin but also an amazing teacher. She would say just a few sentences, and suddenly everything was clear. Or she would demonstrate how to play. At that

point, it all depends on the student’s ability to recreate—not copy, mind you; that is a different thing. You cannot copy and be natural. You need to construct the idea the teacher is trying to present. Also, in Chopin’s music, there is a fine line between being sensitive and being overly sensitive. Many students make a mistake thinking that since Chopin is a Romantic composer, they can take much freedom while interpreting his music. However, that’s often not true.

Vera Gornostayeva was your teacher at the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory. What was so unique about her?

She had this special feeling for the music of Chopin, also for other Romantic composers. She was an excellent teacher of Schumann and Liszt, too, and all Romantic repertoire. She immediately sensed what the student needed. She was also very expressive with the language, drawing parallels to literature and art and explaining the images she wanted the student to envision while playing Chopin’s music. To me, this was invaluable. She would, for example, say that this passage is like a breath of fresh air. Right away, everything I played sounded completely different. So that was her strength. She had a lot of imagination. She did not just focus on the craftsmanship. She talked more about the music, about images, about the sense of Chopin’s music, more about what the music expressed rather than the technicality of it. Of course, she would instruct how to touch the piano, how to achieve legato, for example, but that was secondary. First of all, she taught what the music was expressing, what the music meant.

Is this how you teach your students?

Yes, of course, though I tailor my teaching individually to each student. Those who have had solid instruction and have gone to good schools before they come to me—I can definitely do more with those students. I try to influence each student the same way Vera Gornostayeva did when she was teaching me. She was exceptional.

How do you approach Chopin’s compositions?

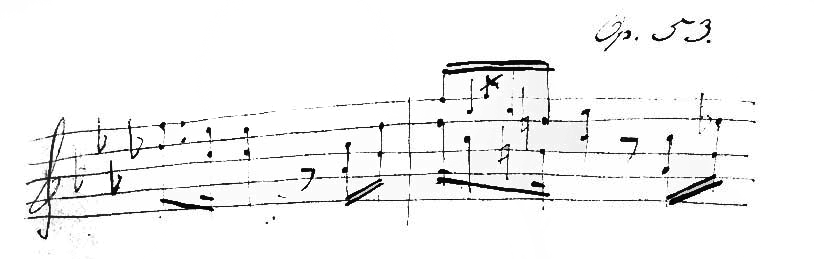

I try to be as precise as possible to what is written in the music, and then, I put it through myself. I try to understand why Chopin wrote a piece in a particular way, why he put an accent here or a crescendo there, and what it’s supposed to mean. Some of the notation, of course, I see as relative, and if I am not convinced, I do something else instead, but still within the context of the music. This is another thing that my teacher taught me: You don’t have to be pedantic. I would not go against the tradition, but there are little things you can do. I try to stay true to Chopin but take a little bit of freedom to interpret it the way I want to. Only then can it sound really fresh.

When one listens, for example, to your recording of Chopin’s Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp minor, Op. 39, you seem to be enjoying the contrasting texture and the juxtaposition of different sounds: light, pearly on the one hand, and majestic on the other.

This particular scherzo has two definitely contrasting images. One is darker and more mysterious or devilish, if you will, and the middle section is dreamier and more lyrical. Likewise, Scherzo No. 4 [in E major, Op. 54] has those sparkling and beautiful images, and then an expressive, deep, dramatic middle section that reflects nostalgia, melancholy, and sadness. It evokes eternal things. With Chopin, it is really important to understand what the music is really about but never overdo it. As an interpreter, it’s a very fine line that you are walking—you are supposed to bring this music to life, but you cannot bring it to life altered.

What in Chopin’s music touches you emotionally?

There is this word “żal” in Polish that describes the quality that touches me most profoundly. This is a unique feature that applies only to his music, and it can be found everywhere—in his mazurkas, in the middle section of scherzos, in several of his nocturnes. It is that special feeling of nostalgia and melancholy; it is something very fragile and sad, but light at the same time.

Does your Русская душа (“Russian soul”) feel a special “Slavic” connection with Chopin?

I would say that everything that corresponds to Slavic folk dances—definitely. For example, rhythms in his mazurkas or his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor [singing] “tam, tadari, da…”—I like that. The playfulness in his music has a lot of resemblance to Russian music. Tchaikovsky is a good example: There is this Russian, “eternal” sadness, this dramatic, profound feeling in his music. In Chopin, though, it is a bit different: Chopin is “aristocratic.” There is always balance in his music, even when it expresses deep emotions. There is always a limit to it. In his music, you won’t find this inflated sobbing, which in Tchaikovsky goes overboard [laughs], like in his Piano Trio in A minor: in the end, you have this [singing dramatically] “taaa dir dira dra dira”—it’s impossible! It’s like sobbing for five pages! This is the Russian soul.

Do you have to know Chopin’s life story to present a convincing interpretation?

Absolutely. You should know the tragedies in his life, which sometimes was dark and painful, which is well expressed in his Mazurka in A minor, Op.17, No. 4 [singing]: “ti, ta, titda dida…” This mazurka starts with the dramatic seventh [interval]. There are a lot of pieces like this: painful and penetrating. At the same time, there is bliss in his music, when he is just carried away, perhaps by a beautiful image of his motherland or some happy times, like in his Nocturne in D-flat major or in the second movement of his Sonata No. 3 in B minor, one of the greatest themes ever written. In the final movement of that sonata, there is a lot of torment, agitation, and confusion. You can relate this to the dark and dramatic times of Polish history.

Many pianists I have interviewed have talked about singing qualities in Chopin’s music, but none has sung during the interview [laughs].

Really? [laughs] Well, this singing quality applies to many Romantic composers. Think of Liszt’s Consolation in D-flat major or Schumann’s “Romanze” from Viennese Carnival, which have a lot of beautiful melodies. Still, Chopin stands apart. He is truly is unique.

Let’s talk about your music education. Did your family support your decision to be a pianist?

I would say so. My mother was a ballet dancer and my grandmother, a piano teacher. They definitely encouraged me to do my best. First, I studied at the Central Music School, which prepared me well for the Moscow Conservatory, where I got the best possible teaching one could get in Russia. I am glad I got the support of my family. But to my credit, I was persistent, too.

What in your music education came to you naturally and what did you have to work hard on?

When I was younger, I did not want to practice. Of course, nobody wants to practice [laughs]. It is still a challenge to fit practice into my everyday routine. It was also hard to learn to perform on stage. This part was not easy; everybody gets anxious on stage. Entering many competitions helped me maintain control during a performance.

What was your main motivation to pursue a music career?

When I was a little girl, I saw all those Russian prize-winners going around the world and playing concerts. I just wanted to be one of them. I met Dina Yoffe when I was only a twelve-year-old girl. She just came from Warsaw, where she won the second prize at the Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition. I sensed success could be available to me if I worked hard enough. It was right there. The whole atmosphere, that sense of belonging to something great was very alluring to me.

Did you have any other interests besides music?

I always loved ballet and watched ballet a lot. I also wanted to sing. During my studies, I took some singing classes from my fellow students who studied voice. I really enjoyed it, and when I came over to America and started to study piano with Sergei Babayan at the Cleveland Institute of Music, I also took voice classes. At some point, I realized that I could not do both and decided to stick with the piano.

Why did you decide to stay in the U.S.?

First of all, because I studied here, and then I won the Cleveland Piano Competition in 1995. Then I won another competition, and I received many offers to concertize. When I got an artist green card, travel became so much easier. For some reason, it was more convenient to build my career out of here than from Russia, especially since Russia was struggling at that time.

How do you find the American audience?

It is very different from the European or Russian audience. American audiences appreciate a different kind of piano repertoire. They tend to like contemporary composers and an exciting, spectacular repertoire.

On a personal level, do you feel assimilated?

Oh, yes, I have been living in the U.S. for 25 years, and I do feel assimilated.

Some pianists decide, at some point, to switch gears from performing to teaching. What are your priorities at this moment of your career?

You need to do both. If you concertize, you are so much more capable of influencing your students. When they see their teacher perform on stage for an hour and a half, they see the final product and feel more motivated. They want to become like their teacher, maybe not exactly like their teacher, but to acquire the same quality and become better pianists. I don’t believe in teaching from the chair. You need to demonstrate what you want them to achieve. Besides, you can’t make a living by playing concerts only, unless you play a hundred and fifty concerts a year, which, of course, is impossible. It is difficult to sell classical music nowadays, even by household names. Teaching simply gives you a steady income.

Do you have time for anything else?

Not really [laughs]. I am lucky if I can squeeze in three hours of practice every day. While teaching, you need to sacrifice a lot. You want to practice and learn a new repertoire, and then you still spent five hours a day on classroom instruction. A university position also requires you to attend meetings and auditions. And then there is traveling and giving masterclasses. It all takes a lot of energy. But I cannot complain. I feel very fortunate.

Vera Gornostayeva was your teacher at the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory. What was so unique about her?

She had this special feeling for the music of Chopin, also for other Romantic composers. She was an excellent teacher of Schumann and Liszt, too, and all Romantic repertoire. She immediately sensed what the student needed. She was also very expressive with the language, drawing parallels to literature and art and explaining the images she wanted the student to envision while playing Chopin’s music. To me, this was invaluable. She would, for example, say that this passage is like a breath of fresh air. Right away, everything I played sounded completely different. So that was her strength. She had a lot of imagination. She did not just focus on the craftsmanship. She talked more about the music, about images, about the sense of Chopin’s music, more about what the music expressed rather than the technicality of it. Of course, she would instruct how to touch the piano, how to achieve legato, for example, but that was secondary. First of all, she taught what the music was expressing, what the music meant.

Is this how you teach your students?

Yes, of course, though I tailor my teaching individually to each student. Those who have had solid instruction and have gone to good schools before they come to me—I can definitely do more with those students. I try to influence each student the same way Vera Gornostayeva did when she was teaching me. She was exceptional.

How do you approach Chopin’s compositions?

I try to be as precise as possible to what is written in the music, and then, I put it through myself. I try to understand why Chopin wrote a piece in a particular way, why he put an accent here or a crescendo there, and what it’s supposed to mean. Some of the notation, of course, I see as relative, and if I am not convinced, I do something else instead, but still within the context of the music. This is another thing that my teacher taught me: You don’t have to be pedantic. I would not go against the tradition, but there are little things you can do. I try to stay true to Chopin but take a little bit of freedom to interpret it the way I want to. Only then can it sound really fresh.

When one listens, for example, to your recording of Chopin’s Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp minor, Op. 39, you seem to be enjoying the contrasting texture and the juxtaposition of different sounds: light, pearly on the one hand, and majestic on the other.

This particular scherzo has two definitely contrasting images. One is darker and more mysterious or devilish, if you will, and the middle section is dreamier and more lyrical. Likewise, Scherzo No. 4 [in E major, Op. 54] has those sparkling and beautiful images, and then an expressive, deep, dramatic middle section that reflects nostalgia, melancholy, and sadness. It evokes eternal things. With Chopin, it is really important to understand what the music is really about but never overdo it. As an interpreter, it’s a very fine line that you are walking—you are supposed to bring this music to life, but you cannot bring it to life altered.

What in Chopin’s music touches you emotionally?

There is this word “żal” in Polish that describes the quality that touches me most profoundly. This is a unique feature that applies only to his music, and it can be found everywhere—in his mazurkas, in the middle section of scherzos, in several of his nocturnes. It is that special feeling of nostalgia and melancholy; it is something very fragile and sad, but light at the same time.

Does your Русская душа (“Russian soul”) feel a special “Slavic” connection with Chopin?

I would say that everything that corresponds to Slavic folk dances—definitely. For example, rhythms in his mazurkas or his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor [singing] “tam, tadari, da…”—I like that. The playfulness in his music has a lot of resemblance to Russian music. Tchaikovsky is a good example: There is this Russian, “eternal” sadness, this dramatic, profound feeling in his music. In Chopin, though, it is a bit different: Chopin is “aristocratic.” There is always balance in his music, even when it expresses deep emotions. There is always a limit to it. In his music, you won’t find this inflated sobbing, which in Tchaikovsky goes overboard [laughs], like in his Piano Trio in A minor: in the end, you have this [singing dramatically] “taaa dir dira dra dira”—it’s impossible! It’s like sobbing for five pages! This is the Russian soul.

Do you have to know Chopin’s life story to present a convincing interpretation?

Absolutely. You should know the tragedies in his life, which sometimes was dark and painful, which is well expressed in his Mazurka in A minor, Op.17, No. 4 [singing]: “ti, ta, titda dida…” This mazurka starts with the dramatic seventh [interval]. There are a lot of pieces like this: painful and penetrating. At the same time, there is bliss in his music, when he is just carried away, perhaps by a beautiful image of his motherland or some happy times, like in his Nocturne in D-flat major or in the second movement of his Sonata No. 3 in B minor, one of the greatest themes ever written. In the final movement of that sonata, there is a lot of torment, agitation, and confusion. You can relate this to the dark and dramatic times of Polish history.

Many pianists I have interviewed have talked about singing qualities in Chopin’s music, but none has sung during the interview [laughs].

Really? [laughs] Well, this singing quality applies to many Romantic composers. Think of Liszt’s Consolation in D-flat major or Schumann’s “Romanze” from Viennese Carnival, which have a lot of beautiful melodies. Still, Chopin stands apart. He is truly is unique.

Let’s talk about your music education. Did your family support your decision to be a pianist?

I would say so. My mother was a ballet dancer and my grandmother, a piano teacher. They definitely encouraged me to do my best. First, I studied at the Central Music School, which prepared me well for the Moscow Conservatory, where I got the best possible teaching one could get in Russia. I am glad I got the support of my family. But to my credit, I was persistent, too.

What in your music education came to you naturally and what did you have to work hard on?

When I was younger, I did not want to practice. Of course, nobody wants to practice [laughs]. It is still a challenge to fit practice into my everyday routine. It was also hard to learn to perform on stage. This part was not easy; everybody gets anxious on stage. Entering many competitions helped me maintain control during a performance.

What was your main motivation to pursue a music career?

When I was a little girl, I saw all those Russian prize-winners going around the world and playing concerts. I just wanted to be one of them. I met Dina Yoffe when I was only a twelve-year-old girl. She just came from Warsaw, where she won the second prize at the Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition. I sensed success could be available to me if I worked hard enough. It was right there. The whole atmosphere, that sense of belonging to something great was very alluring to me.

Did you have any other interests besides music?

I always loved ballet and watched ballet a lot. I also wanted to sing. During my studies, I took some singing classes from my fellow students who studied voice. I really enjoyed it, and when I came over to America and started to study piano with Sergei Babayan at the Cleveland Institute of Music, I also took voice classes. At some point, I realized that I could not do both and decided to stick with the piano.

Why did you decide to stay in the U.S.?

First of all, because I studied here, and then I won the Cleveland Piano Competition in 1995. Then I won another competition, and I received many offers to concertize. When I got an artist green card, travel became so much easier. For some reason, it was more convenient to build my career out of here than from Russia, especially since Russia was struggling at that time.

How do you find the American audience?

It is very different from the European or Russian audience. American audiences appreciate a different kind of piano repertoire. They tend to like contemporary composers and an exciting, spectacular repertoire.

On a personal level, do you feel assimilated?

Oh, yes, I have been living in the U.S. for 25 years, and I do feel assimilated.

Some pianists decide, at some point, to switch gears from performing to teaching. What are your priorities at this moment of your career?

You need to do both. If you concertize, you are so much more capable of influencing your students. When they see their teacher perform on stage for an hour and a half, they see the final product and feel more motivated. They want to become like their teacher, maybe not exactly like their teacher, but to acquire the same quality and become better pianists. I don’t believe in teaching from the chair. You need to demonstrate what you want them to achieve. Besides, you can’t make a living by playing concerts only, unless you play a hundred and fifty concerts a year, which, of course, is impossible. It is difficult to sell classical music nowadays, even by household names. Teaching simply gives you a steady income.

Do you have time for anything else?

Not really [laughs]. I am lucky if I can squeeze in three hours of practice every day. While teaching, you need to sacrifice a lot. You want to practice and learn a new repertoire, and then you still spent five hours a day on classroom instruction. A university position also requires you to attend meetings and auditions. And then there is traveling and giving masterclasses. It all takes a lot of energy. But I cannot complain. I feel very fortunate.

1 Vera Gornostayeva (1929-2015) was a renowned teacher at the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory. Many outstanding pianists benefited from her celebrated instruction, including Ivo Pogorelic, as well as pianists the Chopin Society of Atlanta has hosted, such as Dina Yoffe and Sergei Babayan.

Photo by Nannette Bedway

February 20, 2019