Copyright © 2002 - 2018 Chopin Society of Atlanta

The Magic of the Moment

Exclusive Interview with

RAFAŁ BLECHACZ

winner of the International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition and recipient of the Gilmore Artist award

By Bożena U. Zaremba

What defines you as an artist: winning the Chopin Piano Competition, the Gilmore Artist award, or perhaps something else?

Generally speaking, an artist is, first of all, defined by his interpretations, and my “adventure” with music and the process of developing my interpretations began way before the Chopin Competition. I started with the music by Johann Sebastian Bach and other composers; then it was indeed time for Fryderyk Chopin’s music. Of course, there would have been no Chopin Competition if there hadn’t been other competitions, first national and then international. Winning the Chopin Competition was groundbreaking for my international career because I was given an opportunity to show my interpretations to an ever-growing audience, at prestigious concert halls and festivals, including in the United States. My performances also appealed to and were appreciated by the judges of the prestigious Gilmore award.

Do you consider yourself an artistic heir of Krystian Zimerman, who was the latest Polish winner of the Chopin Competition before you?

Exclusive Interview with

RAFAŁ BLECHACZ

winner of the International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition and recipient of the Gilmore Artist award

By Bożena U. Zaremba

What defines you as an artist: winning the Chopin Piano Competition, the Gilmore Artist award, or perhaps something else?

Generally speaking, an artist is, first of all, defined by his interpretations, and my “adventure” with music and the process of developing my interpretations began way before the Chopin Competition. I started with the music by Johann Sebastian Bach and other composers; then it was indeed time for Fryderyk Chopin’s music. Of course, there would have been no Chopin Competition if there hadn’t been other competitions, first national and then international. Winning the Chopin Competition was groundbreaking for my international career because I was given an opportunity to show my interpretations to an ever-growing audience, at prestigious concert halls and festivals, including in the United States. My performances also appealed to and were appreciated by the judges of the prestigious Gilmore award.

Do you consider yourself an artistic heir of Krystian Zimerman, who was the latest Polish winner of the Chopin Competition before you?

This might be a risky statement because every artist has a different personality, draws inspiration from different things, and is a different human being. For sure, we belong to the group of Chopin Competition winners, but we follow separate paths.

But you do keep in touch, right?

Yes, indeed. This contact was especially important after the Chopin Competition in 2005, when Krystian Zimerman sent me a beautiful letter of congratulations, in which he also offered to help. It was a tough period for me because winning the competition created a variety of situations that were entirely foreign to me. Krystian Zimerman’s experience and the many conversations we had were very helpful in giving the proper direction to my post-competition path. A good example would be choosing the right artistic agency.

In the thirteen years that have passed since then, has your attitude toward Chopin’s music changed?

Yes, definitely, though the changes are not massive; nor are they controversial. I think I have a more liberal approach to certain interpretative ideas, or to the choice of tempo. A good example is tempo rubato in mazurkas. Also, a tremendous influence—in addition to my whole artistic and personal development—is the fact that I have been presenting my repertoire at various concert halls, with different acoustics, on a different piano, and in front of different audiences, which always take an active part in building the interpretation. Each composition “grows” onto you, onto your personality, and you get more and more familiar with particular concepts behind it. This is a truly beautiful process, because when you put a particular composition aside (and I am not talking just about Chopin’s music) and get back to it after a year or so, you rediscover it, and you look at it through the prism of your public performances and the experience of playing music by other composers.

You have recorded several CDs with Chopin’s music, including preludes, mazurkas, polonaises, and concertos. What challenges does each form present to the pianist?

Mazurkas and polonaises, as well as the third movements of both piano concertos, were inspired by the characteristic traits of Polish folk music. These are stylized dances, but still, the typical spirit of the Polish folk dances is ever-present and can be distinctly heard. That is why, when playing mazurkas and polonaises, it is imperative to convey the mood and spirit of a particular dance. Choosing the right tempo and other interpretative means of expression is equally vital. Quite often, especially during a piano competition, some pianists treat a mazurka, for example, like a waltz. They are both dances in triple time, but the understanding of the time signature is different, and you need to be aware of this difference when you start working on a given composition. In the case of other genres, such as nocturnes, scherzos or ballades, most crucial is the expression of emotions and imagination. Another important factor is the so-called “Chopinistic style,” and as a winner of the Chopin Competition, I feel obliged to cherish this style and communicate it in the most appropriate manner.

You also put stress on the use of color.

That’s right. Looking for interesting colors and hues to express the character of each composition, choosing the right sound to a particular phrase—all these are crucial elements of the musical performance. The interpretation becomes more appealing and enticing to the audience. I must admit that it was the music by Claude Debussy and other composers of the Impressionistic era that enriched my understanding and the use of color in music.

Last year, you recorded for Deutsche Grammophon the compositions by the master of the masters; namely, Johann Sebastian Bach. It is your first CD with his music. Is this going back to musical roots?

In a way, yes. I played a lot of Bach’s music from the very beginning of my piano education. I was also very much interested in organ music. I loved going to church to listen to it, and sometimes I even tried playing it myself. Now, when I have some free time, I like going to church to play, just for pleasure, and usually it is Bach’s music. It has developed my sense of polyphony, which I notice in music by Chopin and by other composers. So, I am happy that Deutsche Grammophon accepted my idea and released this CD.

You have an exclusive contract with this recording company. Can you tell us more about the collaboration?

Last year, I signed a new contract, an extension for long-term cooperation in new recording projects. I always prepare music that I am fascinated with and which I think I will interpret well. Only then does it make sense and is valuable. I also take into account the compositions that I play at concerts, which are always on my mind. When a concert season is over, and I start to entertain the thought of recording the repertoire I have been playing, I call Deutsche Grammophon and talk to its producer. Discussion follows. We talk about the program, decide whether this is a right moment or if it’s better to wait because someone else has recorded a similar repertoire. When we reach a consensus, the process is fairly swift. What is more, there are no set time limits.

Does this freedom result from your status as an artist or is it a matter of their policy?

Deutsche Grammophon collaborates with many artists, and in general, the company wants them to feel comfortable with what they do, so from what I have seen, they do not put any pressure on the artists. Sometimes they make suggestions, which, by the way, are very good, like the one they gave me right after the Chopin Competition, when they suggested that I not wait too long with the release of a CD so that the audience would not feel disappointed. Deutsche Grammophon knows the classical music market extremely well, but they focus on artistic quality. I have the pleasure of working with excellent producers, who are passionate about classical music. At the same time, they have in-depth knowledge of the repertoire, and there is no need for me ever to convince them to follow my concepts.

Your interpretation of Bach is well-balanced, and the articulation is pure and clear. Is this your key to Bach?

In a sense, yes. You can achieve that by restrained pedaling, for example. I had been looking for the right piano for this recording for quite a while. I could not make up my mind, so I chose two instruments. I recorded some pieces on one piano and the rest, on the other one. Both instruments have a short, bright sound, a little bit similar to the sound of a harpsichord. I also used the natural attributes of a modern Steinway, while making sure I pay due respect to Bach’s notation. I wanted to convey and express Bach’s Baroque and unique style as faithfully as possible.

So the notation establishes the basis and is the starting point. What comes next?

Most of all, I give myself plenty of time to get familiar with the composition, to “grow into” its concepts. The composition “congeals” under your fingers and in your heart; each phrase becomes yours, and the artistic expression, which emanates from the piece, becomes your expression. Artistic intuition also plays an important role, although it is difficult to determine why a particular idea for interpretation seems to be right. You just know. You feel it. Of course, this intuition is being fed by theoretical knowledge, including knowledge about the composer. But the starting point is in the notation. Also, there exists something that is not written down. I am talking here about that space between the notes, where you have more freedom. However, you always need to be aware of the notation, because if you treat this space too liberally, you can make an interpretative mistake and destroy something that should be left intact.

Is it easy for a pianist to spot the moment when his or her reading starts to overshadow the composer’s intentions?

In my view, it is. If you feel close to the composer’s style, you will realize how far you can go. There is another interesting aspect in all this—that is, the magic of the moment during a particular concert. Once, I had a plan for my interpretation, but the performance took a totally unexpected course, or at another time, the polyphonic reading of some musical texture was basically born at the concert. Later, I thought about how this had happened and tried to recreate it in my mind so that I could repeat it at another concert. Sometimes you can manage to do it, sometimes not, because certain moments are acceptable only in certain instances. Every concert is, in fact, unlike any other, not only because we perform at a different concert hall, for a different audience, and we use a different piano, but because there is this something unique and typical for this singular event only. You never know the final shape or sound of your interpretation, and this is the most beautiful thing in this profession.

Did your exploration of Bach’s music enrich your approach to Chopin’s compositions?

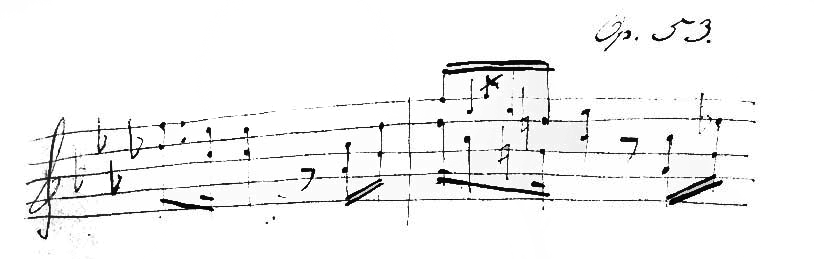

Definitely. Exploring texture and polyphony was very helpful, for example, in reading Polonaise-Fantasie in A major, Op. 61, as well as later mazurkas and nocturnes. When you are conscious of the multi-voiced character of the music, you try to find diverse colors for each voice, for each melody.

Let’s talk about your graduate studies at the Department of Philosophy at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun. Should I address you as Dr. Blechacz?

No, not yet [laughs]. I have not taken the final exam; the defense of my doctoral thesis is yet to be scheduled. I became greatly interested in philosophy in high school, and a few years after the Chopin Competition, when the calendar of my concerts and recordings had been somewhat organized, I thought that it would be good to systematize and formalize my knowledge in philosophy. This was a wonderful adventure—I should say, it is—because this is an extremely extensive subject, and new publications keep coming out on the topics I am mostly interested in—that is, metaphysics, aesthetics, and the philosophy of music. My Ph.D. thesis is on the interpretation of a work of music in the context of phenomenology. The main scientific work I reference in my dissertation is a publication by Roman Ingarden 1, The Work of Music and the Problem of Its Identity, as well as other publications on the philosophy of music. The first part is theoretical and deals with the logic of the work of music. The second part focuses on aesthetical, ethical, and metaphysical values in a particular work of art. This well relates to music by Bach and by Chopin. Further, my research deals with the aesthetical experience—that is, the public concert. My dissertation ends with conclusions that result from my experience with the musical work and touch on such elements as the interpretation and its limits.

Is this somehow connected with what you do, or is it just an intellectual exercise?

It is indeed an intellectual exercise, but this research has, of course, enriched my understanding and outlook on music, as well as on the musical experience—that is, the concert. Ingardens’s work has been very helpful, especially his observation that the audience takes an active part in creating an interpretation. He noted the existence of the so-called initial emotion—the audience’s reaction to first sounds during a concert, which determines the impact of the whole concert.

I have the impression that you have a strong moral backbone. You despise a lie, lack of manners or character, or when people disrespect others. When you meet with arrogance or even hatred, you answer with diplomacy and kindness. Is this your philosophy of life?

“Philosophy of life” might be too far-fetched a phrase, but when you have a clear conscience, a pure mind, and a pure heart, it transfers to what you do as an artist. Your interpretation is authentic and genuine. The audience immediately senses and detects any emotional insincerity.

They say you value privacy; you stay away from the glitz and glamour. During the Chopin Competition, you almost completely distanced yourself from the commotion of the competition. Is this for you the most effective method for a creative atmosphere?

This competition strategy had not been actually pre-planned. I just felt that at that time, this would be best for me. I do not belong to that group of artists who like to compare their interpretations with other people’s performances. I prefer to focus on my own program. Indeed, during the competition, I came to Warsaw only for a specific stage of the event, and then I returned home, where I could collect my thoughts and cool down, where I was able to practice and rest. Later, of course, it was not possible because the media were interested in me and I had to give interviews and take part in press conferences. However, this was absolutely natural for me. Our world demands promotion because, without it, our art would not reach people, and after all, this is the goal of an artist: to share beauty with another human being.

1Roman Ingarden (1893-1970) was a distinguished Polish philosopher whose work focused on phenomenology, ontology, and aesthetics.

But you do keep in touch, right?

Yes, indeed. This contact was especially important after the Chopin Competition in 2005, when Krystian Zimerman sent me a beautiful letter of congratulations, in which he also offered to help. It was a tough period for me because winning the competition created a variety of situations that were entirely foreign to me. Krystian Zimerman’s experience and the many conversations we had were very helpful in giving the proper direction to my post-competition path. A good example would be choosing the right artistic agency.

In the thirteen years that have passed since then, has your attitude toward Chopin’s music changed?

Yes, definitely, though the changes are not massive; nor are they controversial. I think I have a more liberal approach to certain interpretative ideas, or to the choice of tempo. A good example is tempo rubato in mazurkas. Also, a tremendous influence—in addition to my whole artistic and personal development—is the fact that I have been presenting my repertoire at various concert halls, with different acoustics, on a different piano, and in front of different audiences, which always take an active part in building the interpretation. Each composition “grows” onto you, onto your personality, and you get more and more familiar with particular concepts behind it. This is a truly beautiful process, because when you put a particular composition aside (and I am not talking just about Chopin’s music) and get back to it after a year or so, you rediscover it, and you look at it through the prism of your public performances and the experience of playing music by other composers.

You have recorded several CDs with Chopin’s music, including preludes, mazurkas, polonaises, and concertos. What challenges does each form present to the pianist?

Mazurkas and polonaises, as well as the third movements of both piano concertos, were inspired by the characteristic traits of Polish folk music. These are stylized dances, but still, the typical spirit of the Polish folk dances is ever-present and can be distinctly heard. That is why, when playing mazurkas and polonaises, it is imperative to convey the mood and spirit of a particular dance. Choosing the right tempo and other interpretative means of expression is equally vital. Quite often, especially during a piano competition, some pianists treat a mazurka, for example, like a waltz. They are both dances in triple time, but the understanding of the time signature is different, and you need to be aware of this difference when you start working on a given composition. In the case of other genres, such as nocturnes, scherzos or ballades, most crucial is the expression of emotions and imagination. Another important factor is the so-called “Chopinistic style,” and as a winner of the Chopin Competition, I feel obliged to cherish this style and communicate it in the most appropriate manner.

You also put stress on the use of color.

That’s right. Looking for interesting colors and hues to express the character of each composition, choosing the right sound to a particular phrase—all these are crucial elements of the musical performance. The interpretation becomes more appealing and enticing to the audience. I must admit that it was the music by Claude Debussy and other composers of the Impressionistic era that enriched my understanding and the use of color in music.

Last year, you recorded for Deutsche Grammophon the compositions by the master of the masters; namely, Johann Sebastian Bach. It is your first CD with his music. Is this going back to musical roots?

In a way, yes. I played a lot of Bach’s music from the very beginning of my piano education. I was also very much interested in organ music. I loved going to church to listen to it, and sometimes I even tried playing it myself. Now, when I have some free time, I like going to church to play, just for pleasure, and usually it is Bach’s music. It has developed my sense of polyphony, which I notice in music by Chopin and by other composers. So, I am happy that Deutsche Grammophon accepted my idea and released this CD.

You have an exclusive contract with this recording company. Can you tell us more about the collaboration?

Last year, I signed a new contract, an extension for long-term cooperation in new recording projects. I always prepare music that I am fascinated with and which I think I will interpret well. Only then does it make sense and is valuable. I also take into account the compositions that I play at concerts, which are always on my mind. When a concert season is over, and I start to entertain the thought of recording the repertoire I have been playing, I call Deutsche Grammophon and talk to its producer. Discussion follows. We talk about the program, decide whether this is a right moment or if it’s better to wait because someone else has recorded a similar repertoire. When we reach a consensus, the process is fairly swift. What is more, there are no set time limits.

Does this freedom result from your status as an artist or is it a matter of their policy?

Deutsche Grammophon collaborates with many artists, and in general, the company wants them to feel comfortable with what they do, so from what I have seen, they do not put any pressure on the artists. Sometimes they make suggestions, which, by the way, are very good, like the one they gave me right after the Chopin Competition, when they suggested that I not wait too long with the release of a CD so that the audience would not feel disappointed. Deutsche Grammophon knows the classical music market extremely well, but they focus on artistic quality. I have the pleasure of working with excellent producers, who are passionate about classical music. At the same time, they have in-depth knowledge of the repertoire, and there is no need for me ever to convince them to follow my concepts.

Your interpretation of Bach is well-balanced, and the articulation is pure and clear. Is this your key to Bach?

In a sense, yes. You can achieve that by restrained pedaling, for example. I had been looking for the right piano for this recording for quite a while. I could not make up my mind, so I chose two instruments. I recorded some pieces on one piano and the rest, on the other one. Both instruments have a short, bright sound, a little bit similar to the sound of a harpsichord. I also used the natural attributes of a modern Steinway, while making sure I pay due respect to Bach’s notation. I wanted to convey and express Bach’s Baroque and unique style as faithfully as possible.

So the notation establishes the basis and is the starting point. What comes next?

Most of all, I give myself plenty of time to get familiar with the composition, to “grow into” its concepts. The composition “congeals” under your fingers and in your heart; each phrase becomes yours, and the artistic expression, which emanates from the piece, becomes your expression. Artistic intuition also plays an important role, although it is difficult to determine why a particular idea for interpretation seems to be right. You just know. You feel it. Of course, this intuition is being fed by theoretical knowledge, including knowledge about the composer. But the starting point is in the notation. Also, there exists something that is not written down. I am talking here about that space between the notes, where you have more freedom. However, you always need to be aware of the notation, because if you treat this space too liberally, you can make an interpretative mistake and destroy something that should be left intact.

Is it easy for a pianist to spot the moment when his or her reading starts to overshadow the composer’s intentions?

In my view, it is. If you feel close to the composer’s style, you will realize how far you can go. There is another interesting aspect in all this—that is, the magic of the moment during a particular concert. Once, I had a plan for my interpretation, but the performance took a totally unexpected course, or at another time, the polyphonic reading of some musical texture was basically born at the concert. Later, I thought about how this had happened and tried to recreate it in my mind so that I could repeat it at another concert. Sometimes you can manage to do it, sometimes not, because certain moments are acceptable only in certain instances. Every concert is, in fact, unlike any other, not only because we perform at a different concert hall, for a different audience, and we use a different piano, but because there is this something unique and typical for this singular event only. You never know the final shape or sound of your interpretation, and this is the most beautiful thing in this profession.

Did your exploration of Bach’s music enrich your approach to Chopin’s compositions?

Definitely. Exploring texture and polyphony was very helpful, for example, in reading Polonaise-Fantasie in A major, Op. 61, as well as later mazurkas and nocturnes. When you are conscious of the multi-voiced character of the music, you try to find diverse colors for each voice, for each melody.

Let’s talk about your graduate studies at the Department of Philosophy at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun. Should I address you as Dr. Blechacz?

No, not yet [laughs]. I have not taken the final exam; the defense of my doctoral thesis is yet to be scheduled. I became greatly interested in philosophy in high school, and a few years after the Chopin Competition, when the calendar of my concerts and recordings had been somewhat organized, I thought that it would be good to systematize and formalize my knowledge in philosophy. This was a wonderful adventure—I should say, it is—because this is an extremely extensive subject, and new publications keep coming out on the topics I am mostly interested in—that is, metaphysics, aesthetics, and the philosophy of music. My Ph.D. thesis is on the interpretation of a work of music in the context of phenomenology. The main scientific work I reference in my dissertation is a publication by Roman Ingarden 1, The Work of Music and the Problem of Its Identity, as well as other publications on the philosophy of music. The first part is theoretical and deals with the logic of the work of music. The second part focuses on aesthetical, ethical, and metaphysical values in a particular work of art. This well relates to music by Bach and by Chopin. Further, my research deals with the aesthetical experience—that is, the public concert. My dissertation ends with conclusions that result from my experience with the musical work and touch on such elements as the interpretation and its limits.

Is this somehow connected with what you do, or is it just an intellectual exercise?

It is indeed an intellectual exercise, but this research has, of course, enriched my understanding and outlook on music, as well as on the musical experience—that is, the concert. Ingardens’s work has been very helpful, especially his observation that the audience takes an active part in creating an interpretation. He noted the existence of the so-called initial emotion—the audience’s reaction to first sounds during a concert, which determines the impact of the whole concert.

I have the impression that you have a strong moral backbone. You despise a lie, lack of manners or character, or when people disrespect others. When you meet with arrogance or even hatred, you answer with diplomacy and kindness. Is this your philosophy of life?

“Philosophy of life” might be too far-fetched a phrase, but when you have a clear conscience, a pure mind, and a pure heart, it transfers to what you do as an artist. Your interpretation is authentic and genuine. The audience immediately senses and detects any emotional insincerity.

They say you value privacy; you stay away from the glitz and glamour. During the Chopin Competition, you almost completely distanced yourself from the commotion of the competition. Is this for you the most effective method for a creative atmosphere?

This competition strategy had not been actually pre-planned. I just felt that at that time, this would be best for me. I do not belong to that group of artists who like to compare their interpretations with other people’s performances. I prefer to focus on my own program. Indeed, during the competition, I came to Warsaw only for a specific stage of the event, and then I returned home, where I could collect my thoughts and cool down, where I was able to practice and rest. Later, of course, it was not possible because the media were interested in me and I had to give interviews and take part in press conferences. However, this was absolutely natural for me. Our world demands promotion because, without it, our art would not reach people, and after all, this is the goal of an artist: to share beauty with another human being.

1Roman Ingarden (1893-1970) was a distinguished Polish philosopher whose work focused on phenomenology, ontology, and aesthetics.

Photo by

Marco Borggreve