Copyright © 2002 - 2020 Chopin Society of Atlanta

“When the Head Leads the Fingers”

Interview with Stanisław Drzewiecki and Professor Jarosław Drzewiecki, two generations of pianists: the son and the father. Stanisław Drzewiecki is a winner of the 2000 Eurovision Young Musicians competition.

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Interview with Stanisław Drzewiecki and Professor Jarosław Drzewiecki, two generations of pianists: the son and the father. Stanisław Drzewiecki is a winner of the 2000 Eurovision Young Musicians competition.

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Bożena U. Zaremba: At the age of six, you went on your first concert tour to Japan, accompanied by the prestigious Sinfonia Varsovia Orchestra; at the age of twelve, you won Grand Prix at the European Television Festival in Alicante, Spain; and the next year, in 2000, you won the Grand Prix at the 10th Eurovision Contest for Young Musicians in Bergen. Did you ever have a so-called normal childhood?

Stanisław Drzewiecki: Every childhood is different; everyone has different experiences and needs. While studying music you are a loner, but it does not mean you need to avoid social interaction. Maybe I had less time to play with my friends, but I had a chance to meet fantastic musicians, visit wonderful places, and, most of all, I had great satisfaction sensing how people were moved by my performance. That’s the best prize for grueling and lonely hours of practice.

Jarosław Drzewiecki: We never treated our son in an exceptional way. I think he felt that his life was not much different from that of other people, and, at some point, he probably thought that everyone in the whole world played the piano [laughs].

Stanisław Drzewiecki: Every childhood is different; everyone has different experiences and needs. While studying music you are a loner, but it does not mean you need to avoid social interaction. Maybe I had less time to play with my friends, but I had a chance to meet fantastic musicians, visit wonderful places, and, most of all, I had great satisfaction sensing how people were moved by my performance. That’s the best prize for grueling and lonely hours of practice.

Jarosław Drzewiecki: We never treated our son in an exceptional way. I think he felt that his life was not much different from that of other people, and, at some point, he probably thought that everyone in the whole world played the piano [laughs].

He was not a “child prodigy” for you, then?

JD: I have never liked this phrase, but the media need it and the audience need it; you can’t do much about it. Young people will always succeed if they build their careers on inner harmony. I really admire Stanisław for being humble about what he feels to be his service to the composer and the audience.

Your professional career was in a way determined by family tradition. Did you ever ask yourself if this was what you wanted to do?

SD: This is only partially true. My parents did not actually encourage my music education. It was a teacher friend who wanted to try some fun piano stuff with me. My parents felt like they couldn’t say “no,” and that’s how it all started. And if you do what you really like, it is never hard. Of course, there are moments when I need a break.

What about your formal training?

SD: It started with Professor Ida Leszczyńska, who, after two years, moved to Chicago, where she has achieved great success as a teacher. Then it was Professor Wiera Nosina, and in the last few years, I have been studying with my mother, Professor Tatiana Shebanova 1, a great artist, whose repertoire embraces almost the whole piano literature. This has been a very inspiring phase for me. I have had a chance to study great Romantic composers like Chopin, Liszt, Schubert, Schumann, and Rachmaninoff. My discussions with my mom-teacher have often been very heated, but we always reached consensus. At the same time, I had a chance to “practice” the art of diplomacy to carry out my ideas.

Sometimes you perform together.

SD: Oh, yes! We have played family concerts in Canada, Japan, Portugal, Holland, and Russia. In New York, we played Rachmaninoff’s Waltz for Six Hands. This was fun! This year, we are celebrating the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. For this occasion, we released a new CD with Sinfonia Varsovia, conducted by Michael Zilm. We are also preparing an unusual project, a tour of 16 concerts around Poland, with Mozart’s concertos for one, two, and three pianos and orchestra. We will be using superb Blüthner pianos, and the company will transport the instruments to each Polish city during our tour.

Do you, as a music teacher, have a special method that has proven right?

JD: Every teaching process is different, because every student is different, and I always try to create the best scenario for each one. From my experience, I know that such qualities as versatility, curiosity, temperament, and ability to concentrate are very important and help in developing musical skills. I am against the Suzuki method, and I think that working on manual skills needs to go side by side with emotional development and most of all with expanding the student’s imagination. Composers have embraced in their work the whole palette of human feelings, from the most dramatic to the happiest, but the performer does not need to have experienced them all. It is the imagination and intuition that come in handy.

When is a student ready to “face the world”?

JD: Performing on stage should start from the earliest possible age, so that the young student can gradually get accustomed to and befriend—not fear—the audience. Later on, the responsibility rises and stage fright comes in, but the positive attitude remains. But if we are talking about professional performing, the student is ready when the head starts to lead the fingers; that is, when the student consciously controls the process of artistic creation.

How do you deal with stage fright?

SD: Stage fright, in the common understanding, is an “unclean conscience,” which arises from insufficient preparation. Obviously, when you don’t know your notes you fear you may lose control. For me, stage fright is when every single part of me gets mobilized. It’s a force that releases superhuman power enabling you to “move mountains.” The mind works better thanks to this force.

What did you have to give up to devote your life to music?

SD: Music is my life, but I still have a lot of “outside” hobbies, which do affect how I see the world. I believe you need to expand your horizons as much as possible.

Can you tell us something about your hobbies?

SD: I have learned to fly, and I love diving and plane modeling. Recently I designed a virtual town, with all infrastructures, including an airport and public transport. A few years ago, I designed a hybrid airplane, which, besides some complex designs, has a…concert hall. I do all of this in my free time, of which I have less and less.

In recent years, you have devoted much time to composing music.

SD: I do not aspire to be a composer, but I feel I have always been creating music, and there are moments when writing music feels like a necessity. These are strange, not fully comprehensible moments. When I was a child, it was my mom who wrote down my “compositions.” Although I knew harmony and rhythm, I could not write down the notation. I wrote my first composition, Waltz in A minor, when I was seven. The Eurovision Competition called for a contemporary piece, which I did not have in my repertoire, so I wrote my own, a Prelude Insect. I have also written some pieces for small ensembles, the most notable being music for staging Goethe’s poem, “The Alder King” at the Lalka Theater in Warsaw. This show received the Grand Prize at the International Theater Festival in Poznań. Last March, my new composition, Double Concerto for violin, piano, and orchestra debuted at the Koszalin Philharmonic. Maestro Peter Dabrowski, from Valley Symphony Orchestra in Texas, conducted the concert. This piece is based on folk music from all over the world, including the Far East, Gypsy music, and the music of the Polish Tatra Mountains.

You have won prestigious international competitions, your concert tour takes you to the most prominent concert halls in the U.S., such as Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and you regularly play in Japan. Which experience do you cherish most?

SD: Definitely the Tenth Eurovision Competition in Bergen, Norway, which was shown live in 24 countries. I represented Polish Television and was honored to receive the Grand Prix from Maestro Esa-Pekka Salonen and Prince Haakon, now King of Norway. Just before the final concert, I was told that 10 million people would be watching. This was such an abstract number for me that I was not impressed at all. It was only at the airport that I felt the power of the media, when strangers came up to me to offer congratulations.

What gives you the greatest artistic satisfaction?

SD: When I start to “feel” the composer as if it were me who were composing his music. This was the case with Mozart, Chopin, and Rachmaninoff. Concerts give me an opportunity to share my fascinations with the audience.

What is your attitude towards the interpretation of Chopin’s music?

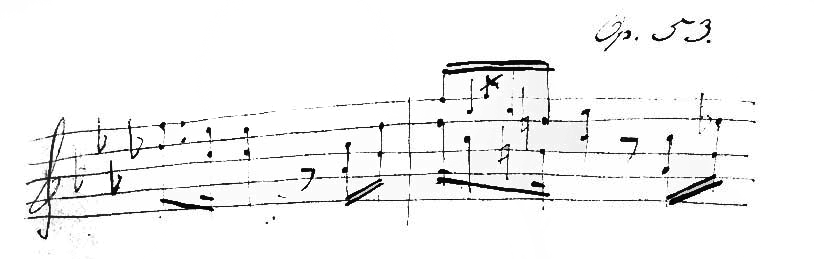

SD: Of course, the pianist needs to present his or her own vision, but I definitely prefer interpretation close to Chopin’s vision, based on his notation and his written texts.

One of the last International Chopin Piano Competition jurors said that you “need to play in accordance with Chopin’s personality, to remember what kind of person he was. To read his letters, look at his portraits. Meditate his life, and find his voice within yourself.” What do you as a teacher think about this?

JD: Knowledge is always helpful in finding the composer’s intentions. Chopin’s letters to his family and friends are the most interesting resource. They show us his true image, not so idealistic as in formal biographies.

What fascinates you most in Chopin’s music?

SD: Constantly shifting moods, like euphoria changing into nostalgia, and the vast array of human emotions. I try to “tune in,” to understand those emotions, and then pass them on to the audience convincingly.

November 28, 2005

Stanisław Drzewiecki’s concert took place on March 19, 2006, at the Roswell Cultural Arts Center in Roswell, Georgia.

1 Tatiana Shebanova died in 2011.

JD: I have never liked this phrase, but the media need it and the audience need it; you can’t do much about it. Young people will always succeed if they build their careers on inner harmony. I really admire Stanisław for being humble about what he feels to be his service to the composer and the audience.

Your professional career was in a way determined by family tradition. Did you ever ask yourself if this was what you wanted to do?

SD: This is only partially true. My parents did not actually encourage my music education. It was a teacher friend who wanted to try some fun piano stuff with me. My parents felt like they couldn’t say “no,” and that’s how it all started. And if you do what you really like, it is never hard. Of course, there are moments when I need a break.

What about your formal training?

SD: It started with Professor Ida Leszczyńska, who, after two years, moved to Chicago, where she has achieved great success as a teacher. Then it was Professor Wiera Nosina, and in the last few years, I have been studying with my mother, Professor Tatiana Shebanova 1, a great artist, whose repertoire embraces almost the whole piano literature. This has been a very inspiring phase for me. I have had a chance to study great Romantic composers like Chopin, Liszt, Schubert, Schumann, and Rachmaninoff. My discussions with my mom-teacher have often been very heated, but we always reached consensus. At the same time, I had a chance to “practice” the art of diplomacy to carry out my ideas.

Sometimes you perform together.

SD: Oh, yes! We have played family concerts in Canada, Japan, Portugal, Holland, and Russia. In New York, we played Rachmaninoff’s Waltz for Six Hands. This was fun! This year, we are celebrating the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. For this occasion, we released a new CD with Sinfonia Varsovia, conducted by Michael Zilm. We are also preparing an unusual project, a tour of 16 concerts around Poland, with Mozart’s concertos for one, two, and three pianos and orchestra. We will be using superb Blüthner pianos, and the company will transport the instruments to each Polish city during our tour.

Do you, as a music teacher, have a special method that has proven right?

JD: Every teaching process is different, because every student is different, and I always try to create the best scenario for each one. From my experience, I know that such qualities as versatility, curiosity, temperament, and ability to concentrate are very important and help in developing musical skills. I am against the Suzuki method, and I think that working on manual skills needs to go side by side with emotional development and most of all with expanding the student’s imagination. Composers have embraced in their work the whole palette of human feelings, from the most dramatic to the happiest, but the performer does not need to have experienced them all. It is the imagination and intuition that come in handy.

When is a student ready to “face the world”?

JD: Performing on stage should start from the earliest possible age, so that the young student can gradually get accustomed to and befriend—not fear—the audience. Later on, the responsibility rises and stage fright comes in, but the positive attitude remains. But if we are talking about professional performing, the student is ready when the head starts to lead the fingers; that is, when the student consciously controls the process of artistic creation.

How do you deal with stage fright?

SD: Stage fright, in the common understanding, is an “unclean conscience,” which arises from insufficient preparation. Obviously, when you don’t know your notes you fear you may lose control. For me, stage fright is when every single part of me gets mobilized. It’s a force that releases superhuman power enabling you to “move mountains.” The mind works better thanks to this force.

What did you have to give up to devote your life to music?

SD: Music is my life, but I still have a lot of “outside” hobbies, which do affect how I see the world. I believe you need to expand your horizons as much as possible.

Can you tell us something about your hobbies?

SD: I have learned to fly, and I love diving and plane modeling. Recently I designed a virtual town, with all infrastructures, including an airport and public transport. A few years ago, I designed a hybrid airplane, which, besides some complex designs, has a…concert hall. I do all of this in my free time, of which I have less and less.

In recent years, you have devoted much time to composing music.

SD: I do not aspire to be a composer, but I feel I have always been creating music, and there are moments when writing music feels like a necessity. These are strange, not fully comprehensible moments. When I was a child, it was my mom who wrote down my “compositions.” Although I knew harmony and rhythm, I could not write down the notation. I wrote my first composition, Waltz in A minor, when I was seven. The Eurovision Competition called for a contemporary piece, which I did not have in my repertoire, so I wrote my own, a Prelude Insect. I have also written some pieces for small ensembles, the most notable being music for staging Goethe’s poem, “The Alder King” at the Lalka Theater in Warsaw. This show received the Grand Prize at the International Theater Festival in Poznań. Last March, my new composition, Double Concerto for violin, piano, and orchestra debuted at the Koszalin Philharmonic. Maestro Peter Dabrowski, from Valley Symphony Orchestra in Texas, conducted the concert. This piece is based on folk music from all over the world, including the Far East, Gypsy music, and the music of the Polish Tatra Mountains.

You have won prestigious international competitions, your concert tour takes you to the most prominent concert halls in the U.S., such as Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and you regularly play in Japan. Which experience do you cherish most?

SD: Definitely the Tenth Eurovision Competition in Bergen, Norway, which was shown live in 24 countries. I represented Polish Television and was honored to receive the Grand Prix from Maestro Esa-Pekka Salonen and Prince Haakon, now King of Norway. Just before the final concert, I was told that 10 million people would be watching. This was such an abstract number for me that I was not impressed at all. It was only at the airport that I felt the power of the media, when strangers came up to me to offer congratulations.

What gives you the greatest artistic satisfaction?

SD: When I start to “feel” the composer as if it were me who were composing his music. This was the case with Mozart, Chopin, and Rachmaninoff. Concerts give me an opportunity to share my fascinations with the audience.

What is your attitude towards the interpretation of Chopin’s music?

SD: Of course, the pianist needs to present his or her own vision, but I definitely prefer interpretation close to Chopin’s vision, based on his notation and his written texts.

One of the last International Chopin Piano Competition jurors said that you “need to play in accordance with Chopin’s personality, to remember what kind of person he was. To read his letters, look at his portraits. Meditate his life, and find his voice within yourself.” What do you as a teacher think about this?

JD: Knowledge is always helpful in finding the composer’s intentions. Chopin’s letters to his family and friends are the most interesting resource. They show us his true image, not so idealistic as in formal biographies.

What fascinates you most in Chopin’s music?

SD: Constantly shifting moods, like euphoria changing into nostalgia, and the vast array of human emotions. I try to “tune in,” to understand those emotions, and then pass them on to the audience convincingly.

November 28, 2005

Stanisław Drzewiecki’s concert took place on March 19, 2006, at the Roswell Cultural Arts Center in Roswell, Georgia.

1 Tatiana Shebanova died in 2011.

Photo by Łukasz Król